The Dress Act of 1746

- lindseynvanwyk

- Dec 3, 2020

- 13 min read

A Brief History of Scotland

In 6,000 BC the people living in Scotland were primitive hunter gatherers, in 4500 BC farming began leading into the Neolithic age. As of 1800 BC, in the Bronze Age residents were talented with stone working and created large stone monoliths.

Stonehenge was built in 1848 BC

After the Bronze Age was the time of the Picts and the Scots. The Picts were a people occupying the Scottish area who were farmers of livestock and various crops like wheat, rye and barley. They also fished and hunted. The Picts were accomplished jewelry makers and created intricately detailed artworks.

The Roman Invasion

Written history begins when the Romans invaded in 80 AD. After 50 years of invasion in 123 AD Emperor Hadrian built a wall to keep out the Picts. It became known as Hadrian’s wall and to this day remnants of it can be seen in the Scottish Countryside.

In 140 AD a second attack reached farther north and in 142 AD the Antonine Wall was begun. After 50 years of fighting the Romans were eventually forced south and after 196 AD Hadrian’s Wall became the southern most border of the area.

In 367 the Picts participated in a raid against England and for a short time existed south of Hadrian’s Wall.

The Founding of Dalriada

In the 6th century the Scot people from Ireland invaded Pictland (what is now Scotland) and founded the kingdom of Dalriada, which was located in the western part of Scotland and at it’s height of power covered Argyll. In 843 the kingdoms of Dalriada and Northumbria merged, but until 1018 southern Scotland was ruled by the English. The Scots conquered and absorbed Strathclude peacefully along with southern Scotland at the Battle of Carham (1018) which also set the River Tweed as the southern boundary of Scotland.

Religion in Ancient Scotland

In the 5th century Christian missionaries began converting the Pict people and building monasteries, including the monastery at Ionia. By the 7th century all of Scotland was Christian.

One of the most famous battles of early Scotland was the attack on the Abbey at Ionia in 795 by Vikings. After this attack where the Abbey was razed the Vikings would go on to settle in the Shetland, Orkney, and Hebrides islands, and the west coast of Scotland.

The History of the Kilt

The feileadh mor (belted plaid or great kilt) emerged in 1594.

(German wood cut ca. 1641, the first picture of kilts.)

According to an anthologist of the time, he came across a group of men wearing the following:

1. A Tartan Plaid (Loose cloak of several ells*, striped and partie colored)

2. Short linen shirt (sometimes saffron colored, evolved78y7 from the leine.)

3. Short jacket.

4. Trews (in the winter) or short hose/stockings (in the summer)

5. Raw leather shoes.

For many years after it’s inception the lowland Scots viewed the Highland Scots as barbarians for wearing the kilt.

(* 1 ELL is equal to the length of the arm from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger, it is an ancient measure going back as far as the Bible.)

To tie a plaid the wearer lead on the ground after pleating the middle (until the total length was about 5 feet), laid on the plaid with the selvage edge at the knee, then fastened it with a belt, keeping the pleated back in place. When wearing a great kilt the extra fabric could be wrapped around the body

in a variety of ways. Offering warmth and ease of movement, the upper fabric could be used as a cloak allowing the tight weave of the fabric to offer some water proofing, and as an added benefit it could be used as a blanket if needing to sleep rough.

The great kilts were made from twill woven worsted wool which gave them an interesting weave pattern. The pattern pictured at right is the Black Watch tartan which is worn by the Highland Regiment of the Royal Army.

What is considered a kilt in the modern times first became popular in 1750, it is known as the small kilt or walking kilt.

The walking kilt, which eventually became the uniform of the Highland regiment in the army, is knee length and has sewn in pleats in the back. It has had the extra fabric above the waistline removed for ease of wearing and movement.

Both the garments (the great kilt, and the walking kilt) were seen as functional garments when they were invented. It is thought that the invention of the kilt may have been due to the boggy, rough terrain in the Scottish highlands.

It is thought that prior to the 1800s the use of a tartan to identify clan loyalties did not exist. During the period when the Dress Act was in effect it’s thought that many patterns (setts), weaving techniques, and dyeing techniques were lost or forgotten within a single generation.

Historical Context Leading to the ’15 and the ‘45

The Scottish Highlands have long been seen as a separate entity to the lowland regions of Scotland. The two main differences between the two were the following:

In the Highlands Gaelic was spoken as the more popular language. To the present day Gaelic is spoken more widely in the Highlands and the Outer Hebrides islands.

The second difference was that north of the Highland Line (denoted in black to the left) the people were arranged into clans with a Laird (who ranks below a Baron but above a gentleman) and the society was tanist while the southern monarchy was (at the time) patrilineal.

As early as 1606 the idea of a union between Scotland and England was an issue in the English Parliament. When King James (who was Scottish) came to the throne in the early 1600s his goal was to combine the two countries under a single flag. While this lead to exciting plots and at one point the attempt to blow up the Houses of Parliament, his desire to see the country united didn’t actually occur until May 1, 1707 with the Articles of Union (now known as the Treaty of Union).

The articles were first proposed in July of 1706 and then separate acts of the parliaments of Scotland and England were necessary to begin the negotiations between the two countries. These negotiations were conducted by 31 commissioners from each parliament. After negotiations the Articles of Union officially went into effect in May 1707.

The treaty ended up being 25 articles including the following:

Article 1: The two countries, “shall upon the first of May... be united into one kingdom by the name of Great Britain.”

Article 2: Provided for the Protestant succession of the house of Hanover.

Article 3: Unification of the Parliament of Great Britain.

Article 4: Freedom of Trade and Navigation within the kingdom.

Articles 5-15, 17, 18: Specific aspects of trade and negotiation ensuring the equality of citizens of both countries.

Article 16: Requirement of common currency.

Article 19: Continuation of Scotland’s separate legal system.

Article 20: The protection (after the union) of inheritable posts, positions, and landholdings.

Article 21: Protection of rights of Royal Burgos.

Article 22: Scotland’s representation in the Parliament with 16 peers and 45 members in the House of Commons.

Article 23: The equivocation of English and Scottish peers.

Article 24: Creation of the Great Seal of Great Britain.

Article 25: All laws inconsistent with the new treaty are declared null and void.

The Treaty of Union was seen as a great success by the people in power. But, the populace had differing opinions, viewing it as, a “political job. Where the Court used economic incentives, patronage, and bribery to secure passage of the union treaty.” (Bowie). There were instances of parliament members being paid off and the Scottish people felt betrayed by their parliament where the pro-union sentiment was the strongest.

In general, the popular opinion was AGAINST the union, the populace saw it as a betrayal because it destroyed the past struggle for a Scottish national identity. According to Bowie, “the idea of incorporation was hated...by the Scottish nation at large.” (Bowie) The members of the Scottish Elite were for the union (due to trade and other economic advantages they would gain) and it was against the wishes of the great majority of people.

Opponents of the Union

There were two main groups of people that were against the Union. The Covenanters, and the Jacobites.

The Covenanters were against the union because it was in direct opposition to their pledges to maintain a Presbyterian based governmental structure, their desire to maintain the purity of the church, and their desire to maintain their preferred style of worship:

their desire to maintain these aspects of their religion and life were some of the reasons the Covenanters were waging war against the English multiple times throughout the 17th century and into the 18th century.

The Jacobites, however, are the beginning of the story of the Dress Act of 1746. The Jacobites backed by the conservative Scottish Highlanders wanted the Stuart king, James II to be returned to the throne. This was against the rules of succession in that he was Roman Catholic, and by this point in England Catholicism had been outlawed (by Henry VIII in 1559).

King James II

In order to understand how King James II helped to lead to the uprisings in 15 and 45, his history is important. King James II ascended to the throne in 1685 becoming the king of Scotland, Ireland, and England. He maintained the throne until 1688 when he was deposed by the Glorious Revolution.

Prior to 1685 he was in the military and as the Lord High Admiral he was responsible for commanding the fleet during the second and third Dutch wars. He was also responsible for the siezing of New Amsterdam and it’s subsequent renaming as New York.

In 1660 he married the daughter of the Earl of Clarendon, Anne, he was a rogue and libertine during this time, but in 1668 or 1669 he joined the Roman Catholic Church. After joining the Roman Catholic Church James became ultra conservative, to the point that in 1673 he resigned all his royal comissions rather than taking an Anti-Catholic oath under the Test Oath Act.

Shortly after this his wife died and he married a Roman Catholic princess, this caused hysteria when around the same time rumors were spreading that a Popish plot was afoot to assassinate Charles to put James on the Throne. Because of This hysteria James went into exile only returning to England in 1682. He resumed his place as the leader of the Anglican Tories by whom he was favored and by 1684 he was highly regarded and there was strong Anglican support. He took the throne in February of 1685.

James II’s Ascention to the Throne

After his ascension the Royalist parliament met in 1685 only to be derailed by rebellions led by the Duke of Monmouth (English) and the Duke of Argyll (Scottish), this led to James forming a deep distrust for his subjects. He put the rebellions down harshly, increased the size of the army, and put Roman Catholic soldiers with experience in charge. This move provoked a fight in Parliament and caused Parliament to be prorogued* in 1685.

(* prorogued- to discontinue a session of Parliament without dissolving it.)

In 1686 division between the king and the Anglican Tories deepened. Many Tories were replaced and

in 1687 James issued the Declaration of Indulgence which suspended laws against Roman Catholic and Protestant dissenters alike. By 1688 there was much confusion over wether these moves were a calculated toleration of religion or wether James wanted to make Roman Catholicism the exclusive religion of Great Britain.

In November of 1687 the Queen fell pregnant which led to the posibility of an heir to the throne

though James’ daughter (Anne) had been the presumed heir. This caused a massive remodeling of the power structure and caused James to get involved in a war in Europe. While his soldiers were in Europe his protestant officers deserted, his daughter Anne defected, and James decided to flee to France.

James attempted to return to England but, he was caught in Kent February 12, 1689, though he was caught by government forces he was allowed to escape a few days later.

Within a few months parliament passed a resolution saying he had abdicated his throne,

offered the throne to William and Mary.

In March of 1689 James left England and landed in Ireland where the Irish Parliament declared him to be king. The Irish/French army was defeated by William in July of 1690 causing James to return to France. By 1697 the Treaty of Rijswyijk between England and France had politically ended his last hope for restoration.

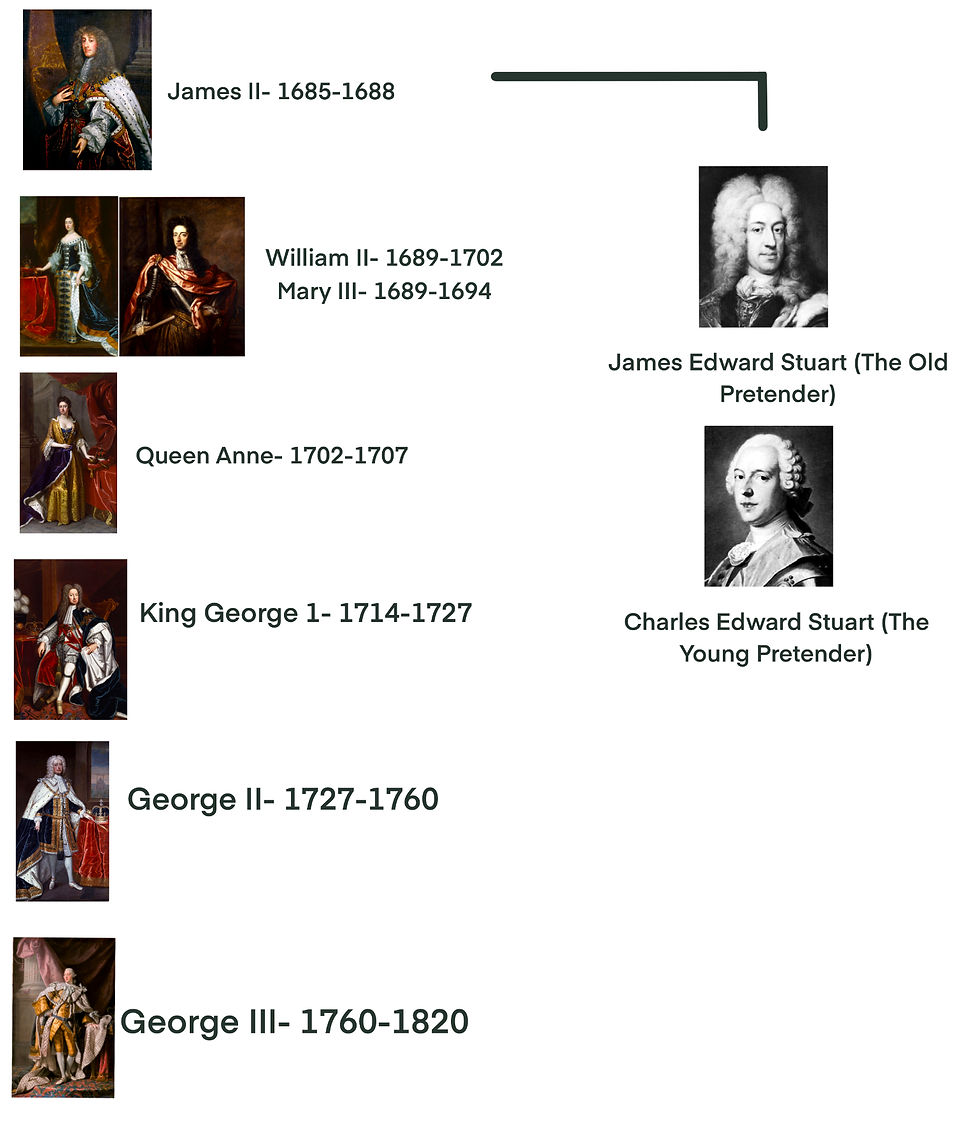

The Pretenders to the Throne

This leads us to the pretenders to the throne, James II and Charles II. James II‘s son, James Edward Stuart (aka- The Old Pretender) was the self-styled James III. William of Orange (Mary’s husband) deposed James II and the infant James Edward was taken to France where he was raised. In 1701 when James II died King Louis XIV declared him King. James Edward’s adherence to Roman Catholicism caused a bill of attainder to be passed in 1701 preventing him from being king. In 1708 he attempted to invade Scotland and in 1714 he refused to renounce Catholicism to become Anne’s rightful heir to the throne. The first Jacobite rebellion in 1715 was caused by the refusal of the crown to accept James Edward’s claim to the throne. It failed in 1716 and James Edward escaped to France. He subsequently married a Polish princess and had Charles Edward.

Charles Edward Stuart and the Rebellion of 1745

Charles Edward (aka. The Young Pretender) was the grandson of James II, and his only aim was to reclaim the ‘stolen’ throne that his grandfather had lost. In 1743 his father, James Edward Stuart, named him as ‘Regent Charles III’ and he set sail for Scotland from France. Upon reaching Scotland he discovered that his previous allies- in France, had decided against sending help to him in order to reclaim the throne of England. He subsequently began raising an army of Highland Scots loyal to his cause, he found much support in the highlands and in 1745 he easily took Edinburgh. He subsequently defeated the government forces in Scotland at Prestonpans.

Flying high on his successes Charles and an army of 6,000 highland men marched to and took Carlisle before complete lack of support from English Jacobites forced them to turn back. George II’s son, the Duke of Cumberland gave chase and caught up with them at Culloden On April 16, 1746. Cumberland massacred Charles’ army with the help of many lowland Scots. As the dust settled Cumberland chased down and killed the fleeing survivors earning him the nickname, “Butcher Cumberland.”

Outcomes of Culloden

The battle of Culloden led to the active passification of the Highland Scot’s nationalism. This was done through a variety of ways, but the most obvious was the Dress Act of 1746. This act outlawed the wearing of any highland clothing,

The underlying reasons for outlawing tartans was to quash rebellions in the wake of Culloden, it also assisted in the dismantling of the clan system, and was created as an attempt to stop another revolt. Tartan was synonymous with the clan system, and plaids were worn as a de facto military uniform for the Highland Scots, and thus, removing the access to the tartan severed their connection with their military identity.

The Dress Act of 1746

The Dress act was first introduced in 1716 as part of The Act of Proscription, and finally passed into law in 1746. It was initially written in the aftermath of the revolt of 1715 and it’s essential points were, the collection of all weapons from Highland Scots and the removal of the ability to wear the plaid unless a member of a royal military unit. Due to the Act of Proscription the use and possession of weapons were also outlawed removing the ability for Highlanders to protect themselves and their properties.

The text of the act read, in part: “ “no man or boy, within that part of Great Britain called Scotland...will wear or put on the clothes commonly called Highland clothes... the plaid, Phil I beg, or little kilt, trousers, shoulder belts, or any part whatsoever of what peculiarity belongs to Hnighland garb; and that no tartan, or party-colored plaid or stuff be used for great coats or upper coats...”.

During the ban, it was only in the Highlands were the citizens were unable to wear plaid, amongst the lowland Scots it was legal to wear a tartan but it was harshly treated. The plaid was banned for 26 years (until 1782) and there were severe penalties for anyone caught wearing one (6 months in prison for a first offense, and transport to a plantation of the Queen for a period of 7 years for a second offense.).

During the 26 year period where the kilt was outlawed the raising of Highland regiments for foreign service promoted the idea of loyalty attached to the idea of the Highland soldier (and subsequently their dress). by 1780 there was little fear of another Jacobite rebellion and the crown moved to restore highland dress to citizens.

Repopularization of the Kilt

The repopularization of the kilt was driven by the monarchy first with Queen Victoria’s ‘Cult of the Highlands’ and the subsequent purchase of the Balmoral estate in Northumberland, and subsequently

with the visit of George II in 1822.

George II visited Scotland and while he was there, wore a kilt. This was chronicled by Sir Walter Scott who was more interested in holding his reader’s attention than he was in creating an accurate representation of the trip, and in his book, Scott included a crowd of be-kilted men in a pageant to impress the king. While undoubtedly colorful, it was fiction that none the less resulted in the wider acceptance of the kilt.

The Repercussions of the Dress Act

The dress act had many effects on Scotland after it was passed into law. The first was the increased emmigration (mostly forced) of Highlander men. The removal of the older generation of people from the Highlands led to a near death of the Gaelic language, as well as the loss of many dyeing and weaving techniques that were used to make plaids and tartans prior to the act.

A second effect that the Dress Act had was the romanticization of the Scottish Highlands. While the tartans were outlawed the ‘Scottish Romantics’ of the age (which was also an age of enlightenment according to some) led to the wearing of the kilt as a form of protest. With this use of the tartan the barbaric Highlanders suddenly became rather, ‘noble savages.’ The romantcization of the Highlands was also a reaction to the increased industry and urbanization of the textile industries in the area which needed a counterbalance which was found in the celebration of the untamed wilderness of the Highlands.

Conclusion

The Dress Act of 1746 had it’s beginnings more than a hundred years earlier in 1606 with the first push for union was sounded. Though it took over 100 years the goal of creating a unified Great Britain was finally achieved in 1707. In spite of numerous uprisings and rebellions, the British government refused to give in to the demands of the minority group of nobles and instead enacted the Dress Act in 1746 in hopes that the removal of the right to bear arms and the loss of the tartan would cause the pacification of the Highland people. While the battle of Culloden was the last battle ever fought on British soil, the heavy losses of the men of the Highland clans left the traditional way of life barely clinging on. Because of the removal of the tartan, weaving and dyeing skills were lost, the subsequent clearances caused the near death of the Gaelic language, and the nationalism for which Scotland was famous was lost and to this day has yet to be found.

Comments